This page is an archive. Its content may no longer be accurate and was last updated on the original publication date. It is intended for reference and as a historical record only. For hep C questions, call Help4Hep BC at 1-888-411-7578.

Prisoners and former prisoners are much more likely to have hepatitis C than the general public; if they didn’t have HCV when they went in, they are likely to contract it there. However, the upside is that prisons are a GREAT place to treat (cure) HCV!

To meet the World Health Organization (WHO)’s goal of eliminating HCV by 2030, individual countries and smaller groups are formulating plans to “micro-eliminate” HCV within their own small group. It would be helpful for them to draw upon the experience of an Australian prison, which demonstrated both feasibility and models of care, as the first prison to actually eliminate hepatitis C.

On October 2, 2018, HepCBC was delighted to attend a Vancouver presentation by Sofia Bartlett, PhD, about her team’s HCV micro-elimination project at a prison in Australia which can be a model for other discrete populations, with particular attention to the specific conditions found in prisons.

Dr. Sofia Bartlett, advertising the WHO goal of NoHEP!

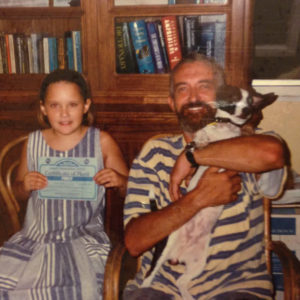

Dr. Bartlett, who participated in a prison’s HCV micro-elimination project, is a lecturer at Australia’s Kirby Institute and currently a postdoctoral fellow at the University of BC and the BC Centre for Disease Control (UBC/BCCDC). Dr. Bartlett’s own father contracted HCV during a period in his twenties (1970’s) in which he injected drugs and was in and out of prison. He has since been cured; this personal history enhanced Dr. Bartlett’s enthusiasm and passion for this lifesaving project which she hopes will serve as a model for many others to come.

Sofia Bartlett and her father in 1996.

How and Why to set Micro-Elimination Goals

WHO’s international HCV elimination goals for 2030 are to reduce new cases by 80% and related deaths by 65%. Because there is no vaccine for HCV, elimination of HCV must rely on targeted treatment and prevention interventions. Breaking down the international and national goals into smaller ones highlights 3 types of target for such micro-interventions:

- Individual at-risk populations such as migrants from high-prevalence countries, indigenous people, people living with common co-morbidities (ex.: HIV, HBV, hemophilia, kidney disease, transplant), prisoners, people who inject drugs (IVDU) or generational cohorts (ex: those born 1945-1975);

- Individual settings, such as a particular hospital, addiction centre or clinic, harm reduction site, hemodialysis clinic, or a prison;

- Geographic areas such as a particular province, city, region, First Nations reserve, or distance from a treatment centre.

The more targeted the treatment and/or prevention intervention is, the more quickly, cheaply, and efficiently elimination can be achieved.

The Demonstration Prison: Lotus Glen Correction Centre in Far North Queensland, Australia

More than 30% of Australia’s male inmate population tests positive for HCV. Lotus Glen Correction Centre (LGCC) has 800 beds for men; 80% of its population identifies as aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander. It includes low, medium, and high security inmates. Inmates are given hepatitis C testing upon entry (they can opt out), and if found positive, all are offered treatment. One nurse on staff has the “Hepatitis Portfolio”; he monitors all patients and serves as a liaison with off-site or visiting nurses, physicians, and pharmacists. A hepatology nurse comes in from Cairns twice a month, and once a month, one of two sexual health physicians visits from Cairns. Upon their release, patients are given a letter to take to their community health care provider detailing their hepatitis status (SVR, need for HCC monitoring or harm reduction, etc.) to ensure seamless engagement with care.

These medical interventions take place within a fully-engaged “Health Promotion Team” including community groups (which are involved starting with the initial planning stage), training for all LGCC staff (open forum and group sessions), and an onsite monthly men’s health group which includes a story-telling (‘yarning’) sharing circle. Key to this is coordination of a region-wide “treatment scale-up” program and a clearly-defined system of linkage to care upon release.

Model of Care: Scale up of treatment with DAAs by a prison Sexual Health Service

119 inmate-patients at LGCC were treated with DAA therapy between Mar. 1, 2016 and Dec. 31, 2017 (22 month period). Median age was 34, 12% had cirrhosis, 75% were treatment-naïve, and the most common genotype (61%) was 3a. Eight different DAA treatment regimens were used, the most common of which (41%) was 12 weeks of sofosbuvir/daclatasvir. Of those who completed treatment and were not lost to follow-up, 97% were cured (achieved SVR-12). The most relevant figure for the goal of elimination is the “Point of Prevalence” figure. HCV Point of Prevalence was 12.52 % at the beginning of the study and 1.07% at the end.

An interesting part of the study detailed the various barriers they encountered, and the practices or solutions that could overcome them. For example, they dealt with the problem of no extra funding by assembling all the resources (including personnel) from multiple services under a common HCV elimination goal to spread the load of achieving it. Other barriers included stigma against coming forward for testing/treatment, frequent transfers to other facilities or release, and inability to prescribe DAA’s on site. Dr. Bartlett gave many examples of how problems were solved; some were creative solutions discovered by inmates. Note the study does not cover the following additional factors critical to elimination:

- Need for long term follow up for monitoring of reinfection and liver disease

- Need for ongoing screening on entry and rapid initiation of treatment

- Need for ongoing provision of harm reduction education and supplies

- Study was not designed to demonstrate Treatment as Prevention impact (requires further baseline incidence data)

Another Model of Care in Australian prisons: Nurse-Led Model of Care (NLMC)

Besides the Sexual Health Service model of care, the Nurse-Led Model of Care is being used in two groups:

(1) New South Wales (NSW) Territory. 38 prisons serving over 12,000 inmates with sentences over 6 months to qualify. 360 patients were treated in the first eight months of DAA roll-out across NSW. The model responds to an inmate diagnosis of chronic HCV thus:

- 75 minutes with a clinical nurse specialist including: Post-test discussion about chronic HCV, various protocol-driven investigations, a focused patient history and Fibroscan. This is followed by

- 5 minutes with a specialist consisting of a virtual (tele-medicine) consultation and prescription, followed by

- As needed, on-treatment monitoring by a clinical nurse specialist.

(2) Victoria (VIC) Territory. 14 prisons serving over 6,000 inmates with sentences over 6 months to qualify. 518 patients were treated in the first 8 months of DAA roll-out across VIC. The treatment was basically the same as in NSW except:

There were 2 full-time nurse specialists which traveled among the 14 institutions with a portable Fibroscan; emphasis was to minimize need for prisoner movement by treating as much as possible locally.

They treated both HCV and HBV.

Interface with supervising hepatologists could be either face-to-face or via tele-medicine.

Dr. Bartlett’s Eight Pillars of HCV micro-elimination success (verbatim quote)

- “Work with marginalized groups leaving no-one who wants treatment untreated

- Spread the workload by educating as many doctors as possible & extending ability to prescribe, including nurses and other health workers as much as possible

- Include the community of those living with HCV from the planning stages

- Ramp up treatment rapidly to reduce HCV incidence (including re-infection)

- Address stigma and discrimination of people living with HCV in health services and correctional centres

- Remove systemic barriers to accessing health services & completing treatment e.g. minimum sentence length eligibility, prescription dispensing fees, etc.

- Spread the word that HCV can be cured easily with new treatments

- Get out of large hospitals and into the community”

What about BC’s correction facilities?

Dr. Bartlett claims that the foundations for HCV micro-elimination in BC’s correctional facilities are already in place, which include:

- Seamless transfer between our province’s prison and community health services under PHSA;

- All past restrictions on DAA treatment eligibility have been removed;

- No restriction on practitioner types eligible to prescribe DAAs (just need pre-authorization)

She also noted BC’s HCV+ numbers are comparable or even lower than the numbers in the referenced Australian territorial prison systems. Current estimates of HCV prevalence in our justice system are:

- Federal level approximately 25% among males, 33% among females

- Provincial level approximately 18% among males, 30% among females. They estimate there are approximately 550 people with HCV infection in BC’s provincial prisons.

Conclusion

In short, we really can do this if we set our minds and energy to it, and all work together on this one simple goal, to eliminate Viral Hepatitis from the world, simply starting WHERE WE ARE. If you are a prison employee or inmate, or a friend, family member, or ally of an inmate, consider joining with others to eliminate hepatitis C in your institution. We have the research now to start successful programs. Dr. Bartlett’s presentation will be put online very shortly. HepCBC will publicize the link as soon as it is available. Note that HepCBC has a Viral Hepatitis Prison Outreach Program which includes visitations to both Federal and Provincial prison health fairs, an education Colouring Book and Art Contest, a brochure, and a toll-free support line. For more information, see http://hepcbc.bchep.org/prisons/ .